Estate Planning Tool: Trust vs. TOD Comparison

Compare Your Estate Planning Options

Answer a few simple questions to see which option better protects your family and assets

Recommendation

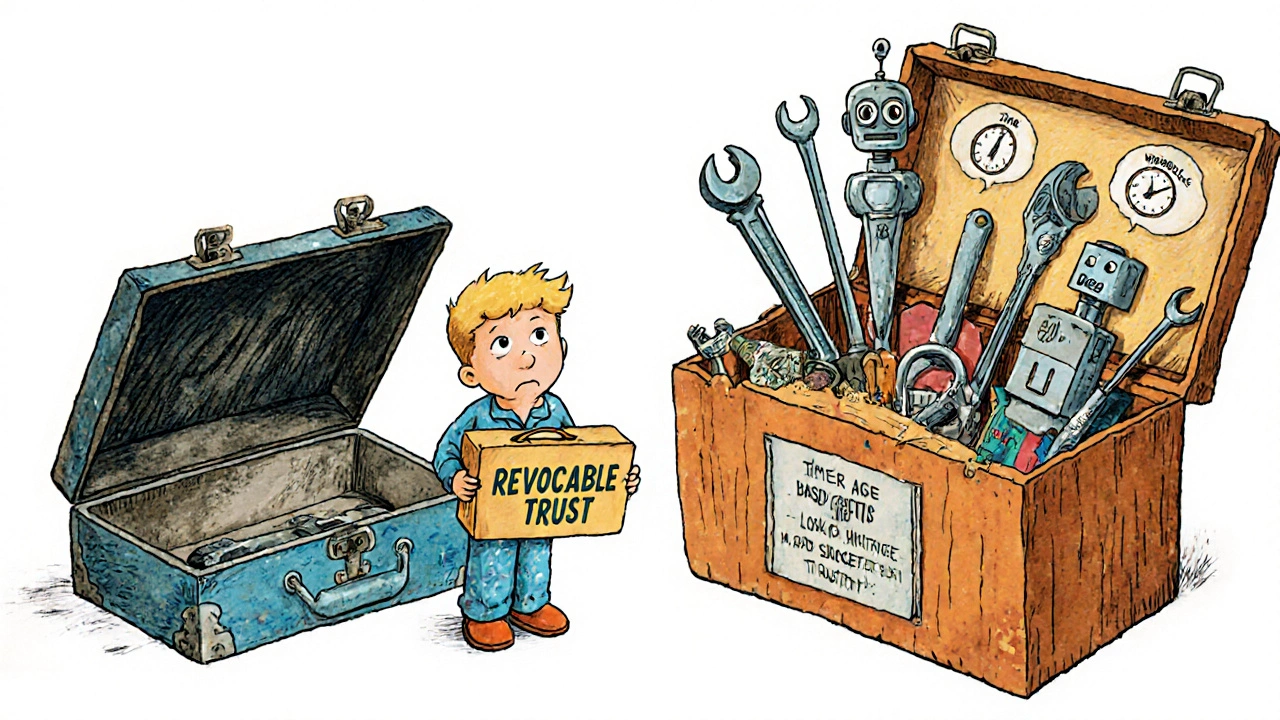

What’s the real difference between a trust and a Transfer on Death deed?

If you’re trying to keep your family out of probate court, you’ve probably heard about Transfer on Death (TOD) deeds and revocable living trusts. Both promise to hand your property to your loved ones without a judge’s involvement. But here’s the truth: trust isn’t just another option-it’s the only tool that gives you real control over your entire estate.

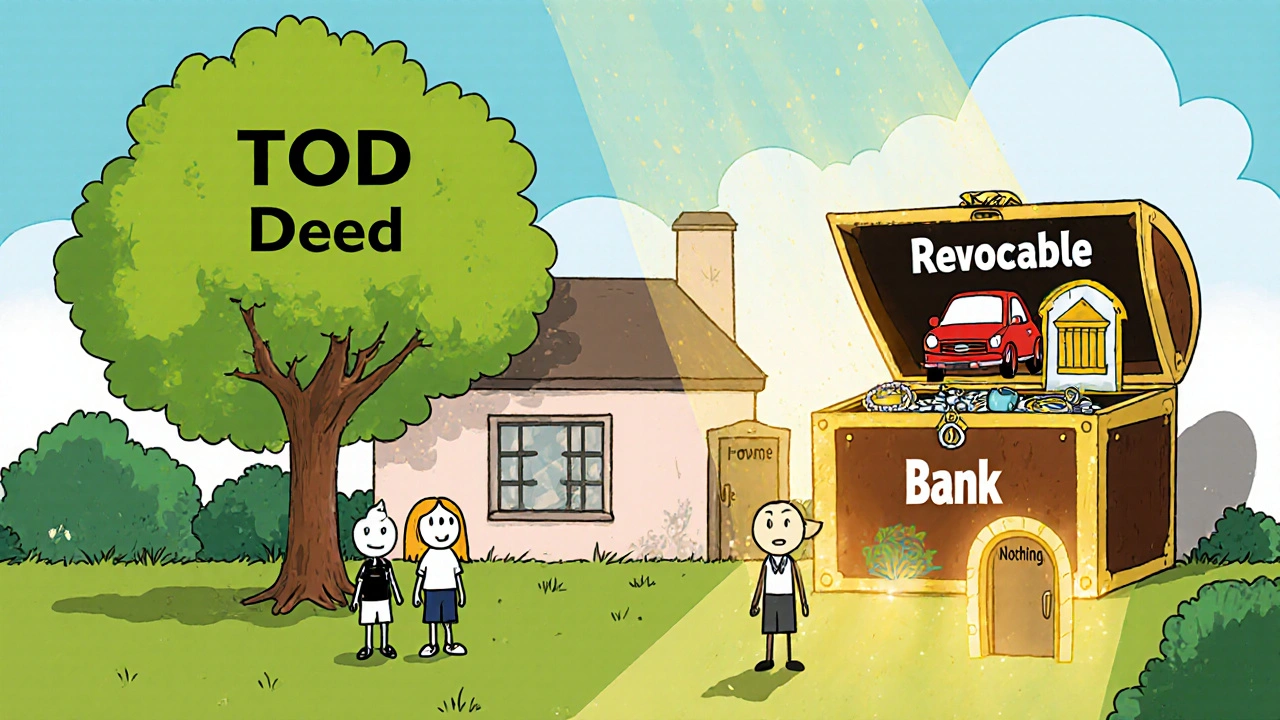

Let’s say you own a house in Colorado and a savings account at your local bank. You put a TOD designation on your house so your daughter gets it when you die. But you never updated your bank account beneficiary form. Five years ago, you named your son as the beneficiary. Now, when you pass, your daughter gets the house, your son gets the bank money, and your other two kids get nothing. No will. No trust. Just confusion, hurt feelings, and maybe even a lawsuit. This isn’t rare. It happens all the time.

Transfer on Death: Simple on the surface, risky underneath

A Transfer on Death deed (TODD) is exactly what it sounds like: a form you file with your county recorder’s office that says, “When I die, give this house to [name].” It’s cheap-usually under $100 to file. You can do it yourself. No lawyer needed. That’s why so many people think it’s the smart move.

But here’s what no one tells you: a TODD only works for real estate. It does nothing for your car, your IRA, your checking account, your jewelry, or your business. And once you file it, you can’t add conditions. No “my daughter gets the house only if she lives in it for two years.” No “my son gets half if he graduates college.” No “hold the property until my grandkids turn 25.” If you want any control over who gets what and when, a TODD won’t help.

And here’s the quiet killer: TODDs aren’t legal in half the country. As of 2025, only 29 states allow them. If you own property in Florida and also have a vacation cabin in Oregon, and Oregon doesn’t recognize TOD deeds? Your Oregon property goes straight to probate. You just wasted your time.

Also, TODDs are public. Once you file it, anyone can walk into the county office and see who you named as beneficiary. If you’re trying to avoid family drama, that’s not helpful. Your sister finds out you left the house to your nephew and suddenly there’s tension at Thanksgiving.

Trusts: The complete estate planning system

A revocable living trust is like a legal container. You put your house, your bank accounts, your investments, even your art collection into it. You stay in control while you’re alive. You can sell, refinance, or give away anything inside the trust-no permission needed. When you die, the trust passes everything you put in it to your chosen people, without probate.

And unlike a TODD, a trust works everywhere. All 50 states recognize revocable trusts. No matter where you own property, the trust covers it. That’s huge if you own homes in multiple states, or if you move later in life.

But the real power is in the details. With a trust, you can say:

- My daughter gets $50,000 when she turns 25, another $50,000 at 30, and the rest at 35.

- If my son is in rehab, his share goes into a protected account managed by my sister.

- My vacation cabin stays in the family-no one can sell it unless all three kids agree.

- If my wife dies before me, the trust shifts control to my daughter as trustee.

You can even name a successor trustee to manage your finances if you become incapacitated. A TODD can’t do that. If you have a stroke and can’t pay your bills, your family has to go to court to get legal authority-unless you have a trust.

Cost and complexity: What you’re really paying for

Yes, a TODD costs less. A simple form, notarization, and a $50 filing fee. Done in an afternoon.

A revocable trust? It costs more. You’ll likely pay $1,500 to $3,500 to have an attorney draft it. Then you have to fund it-meaning you have to change the titles on your house, bank accounts, and investments to the name of the trust. That takes time. You’ll need to call your bank, your brokerage, your title company. It’s not glamorous work.

But here’s what most people don’t realize: the real cost isn’t the upfront fee. It’s what happens when things go wrong.

Think about the Ashley case from OC Trusts Lawyer. She had a trust naming three daughters as equal beneficiaries. But her checking account still had a TOD designation naming only one daughter. When she died, that one daughter withdrew the money. The other two sued. The court had to step in. Legal fees? Over $40,000. Time? Two years. Relationships? Destroyed.

That’s the hidden price of a “simple” TOD. It’s not just about cost-it’s about risk.

Privacy: Keeping your family matters private

Probate is public. If your estate goes through court, anyone can look up your will, your asset list, your beneficiary names, even your debts. Creditors, nosy relatives, even marketers can find your financial details.

A trust? No court. No public record. Everything stays private. Your children don’t have to explain to Aunt Linda why they got $200,000 and your cousin got nothing. Your financial life stays yours.

If you care about dignity, peace, or avoiding family gossip after you’re gone, privacy isn’t a luxury. It’s necessary.

What about hybrid approaches?

Some advisors suggest using a trust as your main plan, then adding TOD designations to a few accounts as a backup. For example, you might put your house and investments in a trust, but use a TOD on your small savings account so it doesn’t get left out.

That sounds smart. But here’s the catch: every time you change one thing, you have to check everything else. If you update your trust to add a new grandchild, did you remember to update the TOD on your credit union account? Did you tell your broker? Did you get the new form signed and filed?

One missed update-and you’ve created a conflict. That’s why most estate attorneys don’t recommend mixing the two unless you’re very disciplined. And even then, you’re still relying on human memory and paperwork. A trust alone, properly funded, is simpler to maintain over time.

Who should use a TOD deed?

There are cases where a TOD deed makes sense:

- You own only one piece of real estate, no other significant assets.

- You’re in a state that allows TOD deeds (check your county recorder’s website).

- You’re confident your beneficiaries won’t fight over the property.

- You’re on a tight budget and can’t afford a trust right now.

Even then, it’s a band-aid. If your estate grows-say you inherit money, sell your house and buy a bigger one, or start a small business-the TOD deed won’t cover it. You’ll end up having to do it all over again.

Who should use a trust?

Use a revocable living trust if:

- You own real estate in more than one state.

- You have more than $100,000 in assets.

- You want to control when and how your heirs receive their inheritance.

- You have minor children, a beneficiary with special needs, or a strained family dynamic.

- You care about privacy and want to avoid public court records.

- You want someone to manage your finances if you become unable to.

It’s not about being rich. It’s about being prepared.

Bottom line: Simplicity isn’t safety

A Transfer on Death deed feels easy. It’s a quick fix. But estate planning isn’t about speed-it’s about certainty. A trust takes more effort upfront, but it protects your family from confusion, conflict, and costly mistakes down the road.

Don’t let the low price of a TOD deed fool you. The real cost is what happens after you’re gone.

If you’re serious about protecting your family, don’t just pick the cheapest tool. Pick the one that actually works for your whole life-not just one piece of paper.

I had no idea TOD deeds didn't work in half the states. I just filed one last year for my condo because it seemed easy. Now I'm sweating. Guess I need to call an estate lawyer before my next birthday.

Also, the part about privacy hit me hard-my sister already knows I left the house to my nephew. She hasn't said anything, but I can feel the tension at family dinners. A trust would've kept that quiet.

Thanks for the wake-up call.

OMG YES. TOD is the financial equivalent of a sticky note on the fridge-‘don’t forget to pay the electric’-but you’re trying to manage a whole damn utility grid.

Trusts are the ERP system for your legacy. You set it up once, automate the payouts, lock down conditions, and boom-your kids don’t have to Google ‘what happens if beneficiary dies before executor’ while crying over their grandma’s china.

Also-$1500? That’s less than a new iPhone. And way less than the $40k legal dumpster fire when your cousin steals the checking account. Do the math, people.

Stop treating estate planning like a DIY home renovation. You’re not fixing a leaky faucet. You’re preventing a family civil war.

This is the most accurate breakdown of estate planning I’ve ever read. I’ve seen too many families torn apart because someone thought a TOD form was ‘good enough.’

My aunt did exactly what the Ashley case did-left her house in a trust but kept a TOD on her savings. Her daughter withdrew $80k the day after the funeral. The other two siblings sued. One of them had a heart attack during the discovery phase.

It’s not about money. It’s about dignity. And control. And not turning your death into a Netflix docuseries titled ‘The Great Inheritance Fight.’

Anyone who says ‘I can’t afford a trust’ is really saying ‘I can’t afford to care about my family after I’m gone.’

While the argument for trusts is compelling and logically structured, I find myself reflecting on the cultural context of inheritance itself. In many societies, including mine in India, wealth is not merely a legal asset but a moral contract between generations. The trust, with its precise clauses and institutional formality, feels like a Western solution to a problem that, in some ways, is not purely financial but existential.

Is it possible that the emotional weight of a handwritten letter, a family gathering to distribute heirlooms, or even the quiet acceptance of unequal shares-rooted in tradition rather than legal enforceability-offers a kind of peace that no trust document can guarantee?

That said, I acknowledge the practical necessity of trusts in modern, mobile, and litigious societies. Perhaps the ideal lies in a hybrid: a trust for assets, and a letter for the soul. Not to control, but to connect. To say, ‘I loved you this way.’ Not ‘I legally willed you this.’

Still, the risk of unintended consequences with TODs is undeniable. I will be updating my own documents this week. Thank you for the clarity.